OVERVIEW

The Térraba are a warrior people that trace its roots back to the pre-Colombian Chiriquí civilization that dominated Costa Rica. When the Spanish Conquistadors arrived in the early 1500s, they found Costa Rica to be a harsh country with few resources to exploit. In comparison to other pre-colonial civilizations, there were few indigenous to use for labor.

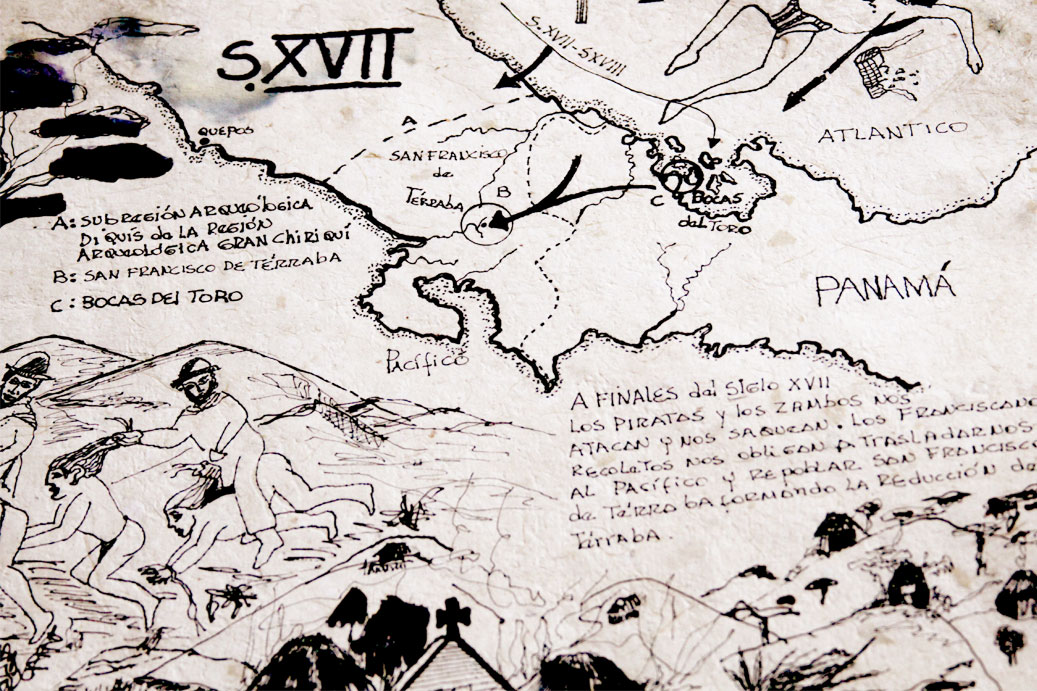

The Spanish brought Catholicism and smallpox, and many tribes were not able to survive both. Despite Spanish influence, the Térraba can trace their history back to specific events as early as the 1600s. The Térraba were able to maintain their culture, traditions and language in spite of the Spanish occupation and Catholic influence. They have recorded an extensive oral history to preserve it for future generations.

The Chiriquí civilization dates back 10,000 years with evidence of caves, rock shelters, and stationary camps that correspond with hunter-gatherer groups. The social and cultural development started then and was at its peak in 600 A.D. until the arrival of the Spaniards at the beginning of the 16th century.

The government has amended and reduced their rights – or ignored them entirely – in the years since implementing the indigenous laws. The Diquís Hydroelectric Project and the trouble in the education system represent the ongoing struggles the Térraba have for rights guaranteed by law.

TIMELINE

1610

The Térraba participated with the indigenous groups Ateos, Viceitas and Cabecares in the rebellion that destroyed Santiago of Salamanca.

1710

Missionaries led by Fray Pablo de Rebullida and the Spanish military moved part of the Térraba population to the southwestern region of Costa Rica, near Boruca and the Térraba River. The town, San Francisco de Térraba, was founded in 1689. Its name was later shortened to Térraba.

1761

The northern Indians attacked San Francisco de Térraba, burning it, killing the men and capturing the women, a day after an attack on Cabagra, another local indigenous group. After the massacre, Térraba only had 300 people left.

1845-1848

After a church was burned, the Catholic priests decided that reducing the territory would conserve and protect the population. Within several years Pauline priests arrived to take over the Térraba community, but brought smallpox. The epidemic decimated the population.

1956-1977

Legislation to establish and protect the indigenous territories gave the Térraba the inalienable right to their traditional land, the use of their resources and some autonomy in self-governance.

1970s

Costa Rica began promoting clearing forests to convert them to agricultural and pastoral lands. Much of the Térraba’s forest was lost.

1982

The Térraba lost the right to own the minerals beneath the soil on their own land, under a new mining law.

1999

Costa Rica recognized indigenous languages in its constitution.

2002

Indigenous communities began protesting against the Diquís Hydroelectric Project, which was then known as the Boruca Hydroelectric Project.

2004

The title to the territory was amended and reduced without asking the Térraba, fragmenting the territory into blocks.

2007

Diquís project workers moved to the region and started work without consulting the Térraba community.

2009

On Oct. 6, more than 150 Térraba and others marched along the inter-American highway to demand respect for their right to participate in decisions involving their lands. They marched all the way to the town of Buenos Aires, more than 8 miles (13 kilometers) from Térraba territory. ICE employees filmed and shouted at them in Buenos Aires, causing a confrontation that required police intervention.

2011

The Costa Rican Electricity Institute (Instituto Costaricense de Electricidad – ICE) removed their equipment and suspended work in Térraba territory.

2012

After feeling that they still weren’t being heard, the Térraba occupied the local school to demand change. The Térraba wanted the right to influence how the students are taught about the culture, and how the language is taught in the schoo